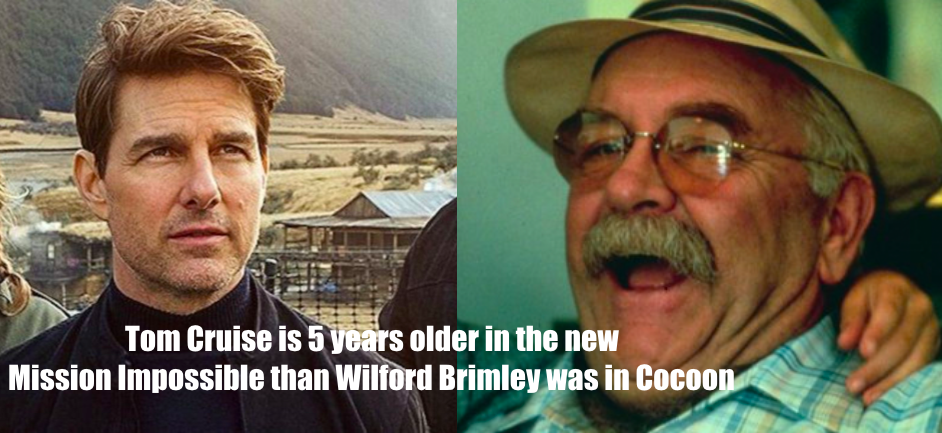

Last month, this meme juxtaposing Tom Cruise and Wilford Brimley’s ages made the internet rounds, leaving innumerable blown minds in its wake. For those who followed up with Wikipedia, it proved true: When he filmed Cocoon in 1984, Brimley was 50 years old; Tom Cruise filmed Mission: Impossible-Fallout at 55. The age comparison between the two men has been circulating for the past few years, updating essentially with every new Mission: Impossible release, but this time it rocketed around social media faster, perhaps because Cruise is now in his mid-50s yet still pulling off his own stunts. In Cocoon, Brimley’s character demonstrated renewed vitality by performing an impressive cannonball. Cruise’s Ethan Hunt spent his most recent mission engaging in sky dive chases and clinging to the side of an Airbus.

This meme matters because of the disbelief it provokes—disbelief over how the face (and body, and actions) of “50-something” have changed in just a few decades. But that’s not because 55-year-olds today feel like Wilford Brimley; studies indicate that, while they aren’t performing death-defying stunts, they’re closer to the active and youthful depictions of not just Cruise but any number of his fellow actors who would now be in the “older adults” demo. The disbelief is in large part due to representation.

However, Mission: Impossible and many other pop culture products feature celebrities 55+ in active roles. It’s advertising where the outdated representation hasn’t yet aged out, so to speak. Formal studies and casual observation of mainstream advertising still situate older adults firmly within a Cocoon paradigm of aging and deterioration. So is our industry a primary driver of the disbelief that fueled this meme, and how can we close the gap between lived age and represented age for our audience members of Tom Cruise’s vintage and above?

(Two quick notes: I’ll use “older adults” to refer to individuals aged 55 and older, as that is the age cut-off employed by a number of studies of this demographic, and also because the two celebrities in the aforementioned meme were both in their early to mid-50s when filmed. Additionally, this article still commits the sin of lumping “older people” together in one cohort, while that shouldn’t be the case considering the vast differences in a group that spans approximately 40 years. Further studies into differences between Baby Boomers and their preceding generations in advertising exist and are very valuable, but not addressed here.)

Age featured prominently in the press surrounding this summer’s release of Mission: Impossible—Fallout, notably in relation to Cruise doing his own stunts. He raced over cobblestones on motorcycles, jumped from airplanes, and held his breath underwater for a seemingly miraculous number of minutes. When he broke his ankle during filming, members of the media went berserk. Despite that stumble, the movie opened to mostly rave reviews and audiences awestruck by his energy. The New York Times’ review hailed the film for that quality even in its title, calling out the Hyper-Human Tom Cruise.”

While much emphasis was placed on Cruise’s apparent cheating of old age, numerous other film stars and celebrities in recent years have demonstrated their vitality over 55 in the public sphere. Denzel Washington and Liam Neeson helm big-budget action films past 60; Madonna and Janet Jackson both headlined major tours in their 50s. Major primetime staples like NCIS, Chicago PD and Law & Order: SVU all feature casts led by 50+ actors who don’t just sit behind desks at the station, but get out and kick ass.

These portrayals of men and women of advanced age keeping up with their younger counterparts exist throughout contemporary popular culture. Except, that is, most advertising. “In their portrayal of older adults,” explain Shyon Baumann and Kim de Laat, “advertising relies on characters that almost never deviate from a narrow range of age-specific behaviors in a straightforward way” (23). These aren’t often explicitly insulting, but are far from liberating. The narrow range exists mostly within the antiquated Cocoon universe that contemporary older adults (and certainly older celebrities) never wrapped themselves in.

This is important because, unlike narrative fiction like cinema and television or celebrity coverage, both of which exist at a remove from “everyday” people, advertising purports to relate to and serve the real world. If the portrayals of populations in ads are limited and out of date, they are unable to change perceptions of and cultural schemas about those populations. Limited depictions of entire generations hobble understanding of those demographic groups for those outside them. Additionally, even people within the demographic being represented then potentially struggle to relate their own wants, needs and abilities to perceived hegemonic, “proper” places and positions in society.

The source of these limited and troubling depictions is the inherently antithetical relationship between aging and American advertising: the industry traditionally plays on aspirational prompts to purchase, yet old age is most often devalued by our culture. “Advertisers manage the devaluation of old age through overall underrepresentation of older adults and by omitting older adults from straightforwardly aspirational advertising,” explain Baumann and Laat (14). The industry’s attitude toward older adults is demonstrated by its two main means of addressing them: denigration or disavowal.

Numerous recent studies analyzing portrayals of older adults in advertising found that individuals in this demographic are seen far less frequently than younger consumers (older women are notably absent), and that those who do appear fall within strict parameters. Aging adults, Baumann and Laat explain, are often framed as having “old” as a condition. “Old” makes them comic or wise, or burdens them with something to fix via medication, supplements, retirement communities, or some other commodified solution. These schemas are far from new, but that very absence of change is precisely why the industry needs to take a new approach to portraying the 55+ demographic. As put by Lauren Crichton in a recent Ad Week call, “It’s time for advertising to stop perpetuating negative stereotypes about aging.”

Beyond the general underrepresentation of older adults in advertising, even when ads feature Baby Boomers and older generations (or products for them), there is a pervasive avoidance of aging. Again, this relates to American culture’s general discomfort with and disavowal of aging. Avoidance takes two notable forms: younger representation and agelessness.

The “mask of aging” hypothesis—that older people think of themselves as younger than they are—explains why marketers use relatively young models to sell self-image-related products to older consumers, with an “underlying assumption being that the bait of youth will lure the older generation” (Crichton). Even for products marketed to explicitly combat ramifications of aging, the models and actors are often demonstrably younger than the target consumer.

“Agelessness” in advertising is an outgrowth of that mask of aging theory, representing older adults as younger than realistic or not calling attention to age at all. Anne L. Balazs sees this as a potentially empowering transition in advertising, serving the desire of the aging population to make the process invisible. Agelessness could then be seen to be self-affirming, but runs the risk of disempowering older adults as their own identity category when represented by models and actors a decade or more younger. This then circles back to erasure as ageism.

So what can advertising learn from the Tom Cruise/Wilford Brimley meme? For one, note the disparity between popular culture and advertising representations of older adults and keep in mind the buying power of this demographic. Baby Boomers have driven innovation and profits in advertising for decades—just because they’re retiring doesn’t mean their impact can be disregarded. Older adults hold the majority of U.S. disposable income. Beyond spending power, the population will continue to resemble Cruise more than Brimley, as “a new paradigm of healthy aging” advances. Misrepresenting this valuable demographic, then, is a bottom-line concern.

Times have changed since Cocoon, and much of popular culture has caught on. Advertising’s lack of counterhegemonic portrayals of older adults will be even more glaring as consumers take media production into their own hands. For example, Crichton hails Instagram’s Instagrannies–women over 60 positioning themselves as influencers on social media, documenting their stylish and active lives, and generally “100 percent slaying.” Advertising needs to catch up.

Finally, we need to stop avoiding aging and instead investigate it. Push beyond preconceived notions about what life over 55 is if you aren’t in that demographic, as so many people in the trenches of planning and creative advertising work are (disclaimer: myself included). Hiring older employees is often easier to say than to do, but consider consultants from diverse demographics, and at minimum ensure qualitative research speaks with the target audience itself. There’s constant buzz about entire agencies devoted to studying and accurately depicting Millennials and Gen Z; spend some of that energy on their grandparents.

Like it or not, we’re all aging. We need to ensure our ads aren’t dated.