Diversity and Marketing

When we talk about diversity in marketing, we first have to identify that we’re talking about target audience diversity—racial, ethnic, and sexual diversity and inclusion. Marketing diversity can refer to a product or geographic diversification. This article is about the inclusion, exclusion, targeting, and stereotyping of women, minorities, and the LGBTQIA+ community and our industry’s efforts to improve. As marketers, our job is to be on the edge but not over the cliff. In college, we were told that we both mirror and mold our zeitgeist. So, while we were subject to the time and cultures of the said past times, we can and should still be judged for the directions we led.

We’ve come a long way, and while there are many things we as marketers have done to advance diversity and inclusion in positive ways, there is still room for improvement. And, our journey has not been without its missteps.

This Plain Talk article on diversity and marketing will recognize the progress made over the past 50 years and address some of the current failings and opportunities.

- Women

- African-Americans

- LGBTQIA+

- Addressing Diversity in Marketing: 3 Questions to Ask

- Get Expert Help With Diversity and Marketing

Women

1930s–2000s: The soaps

As marketers, we were quick to realize the importance of women in decision-making. We even created the first soap opera, “Painted Dreams,” over 90 years ago. This was at a time when only 24.3% of women were in the workforce. Housewives made most of the daily consumer packaged goods (CPG) buying decisions for their nuclear households. In fact, the soap opera was created and even named for its ability to reach women daily with the expressed intent of selling them laundry detergents and other CPGs. Proctor & Gamble produced 20 soap operas. The longest-running soap opera, “Guiding Light,” actually ran contiguously on radio, then TV, for 72 years, ending in 2009. In cultures with high marriage rates and stay-at-home moms, like Latin-X, not born in the U.S. (58%-60%), soap operas are still popular today.

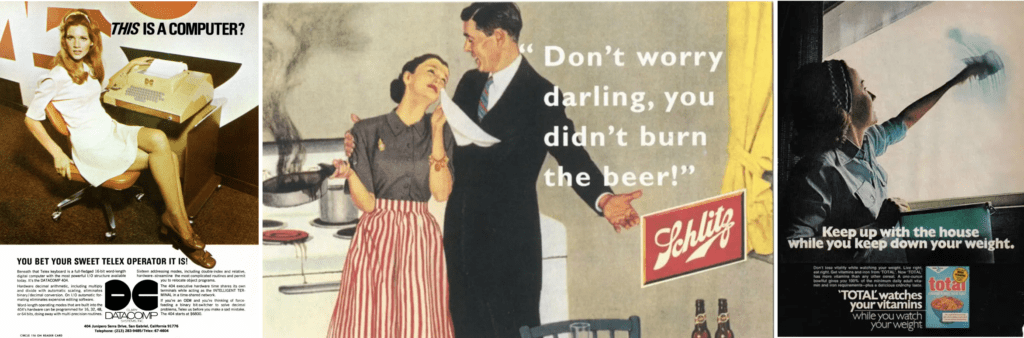

1950s–1970s: Men dominate the advertising industry

Unfortunately, this history of men marketing to housewives led to objectification, stereotyping, and judgment of women, as seen in these ads from the 1950s, 60s, and 70s.

1980s: Pushing the “you can have it all” myth

The percentage of women working out of the home increased from less than one-third in 1948 to over half by the end of 1978. Therefore, ads were developed to target the career woman and her dual role. A popular one that comes to mind are these lyrics from Enjoli perfume: “‘Cuz I’m a woman. Enjoli! I can bring home the bacon. Enjoli! Fry it up in a pan. And never let you forget you’re a man.”

While this jingle is catchy, it helped establish the unrealistic expectation that a woman could do it all. As a 2012 article from HuffPost critiqued:

“I agree with the anti-Enjoli intelligentsia that this idea that women can “have it all” is absurd. In reality, as women like my mother know all too well, what “have it all” meant was that society “allowed” mothers to go to work, but only if they didn’t let their domestic responsibilities slide. So, if by “have it all” you mean two crappy jobs, one that starts at nine and one that starts at five, then yes, you sure could have it all—and an exciting new scent to go with it! Ba-da-da-dum.”

Paul Rasmussen, “Working Moms Can’t Have It All, But At Least They Can Smell Pretty,” HuffPost

Today: Sexism still exists in marketing

Each of the above ads today would be viewed as overtly sexist and inappropriate. But are we still missing the mark that bad? According to Kantar 2019 AdReact, Getting Gender Right Report, while 91% of us marketers think they portray women as positive role models, only 45% of our audiences agree! And even though roughly half of advertising jobs are held by women, the industry is still guilty of viewing women through a male lens. Research shows women don’t want advertising to be judging but rather recognizing, endorsing, and loving.

According to author Jane Cunningham, quoted in The New York Times, August 26, 2021:

“But when you actually talk to women, their aspirations are not, in fact, to be beautiful through the male lens; it’s to feel comfortable in their own skin. It isn’t to be dependent; it’s to maintain their independence, particularly their financial independence. The great female-made brands we talk about in the book (Brandsplaining: Why Marketing is (Still) Sexist And How To Fix It.), like Frida Mom or Third Love, make women feel seen as they are not as men want them to be. That’s the big shift that needs to happen. Brands need to stop telling women how to be and start being in service to them.”

Mara Altman, “Yes, Marketing Is Still Sexist,” The New York Times

In the same article, Cunningham and her coauthor, Philippa Roberts, discuss how age-defying has turned into “ageless,” and dieting has coded itself as “wellness.” They define it as “sneaky sexism” and argue that large brands still don’t get it.

Further, Kantar found far fewer ads featuring women trying to be funny (just 22% vs. 51% featuring men). However, humor improves ad receptivity with both genders more than any other ad characteristic.

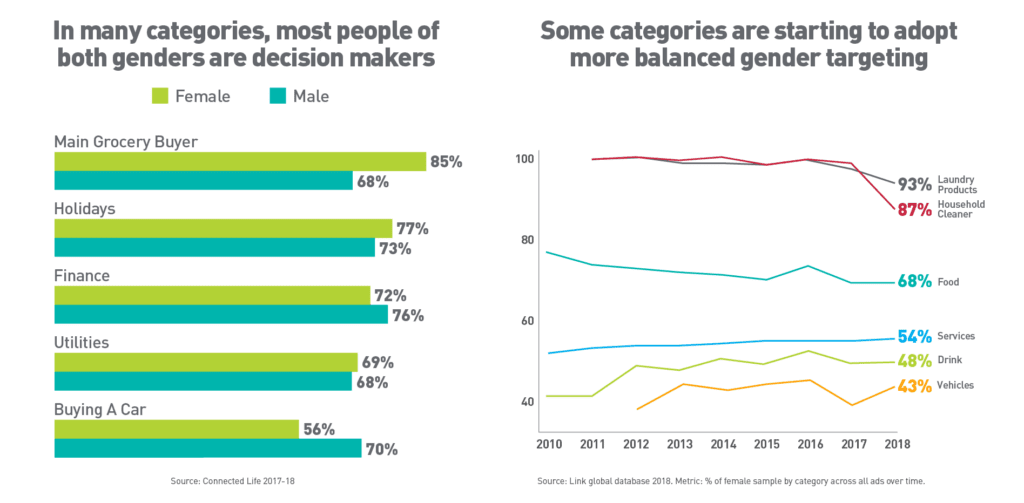

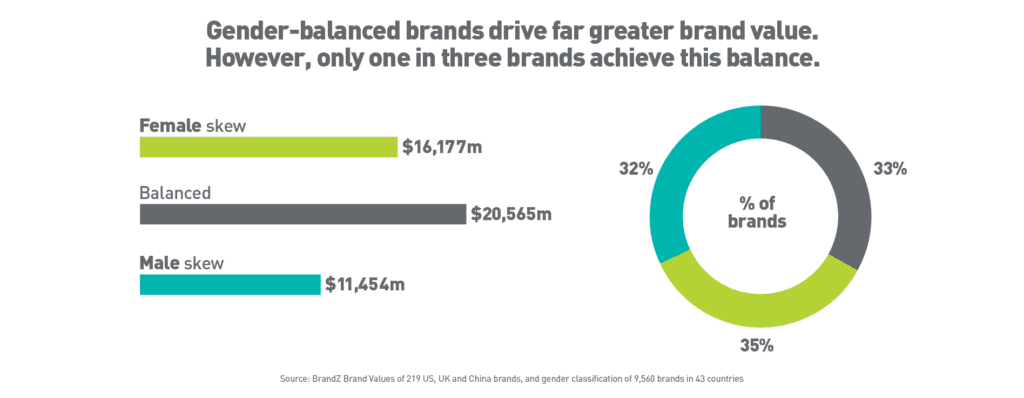

Over-advertising to women

According to the same Kantar report, 98% of household, cleaning, and baby products from 2010–2019 were exclusively marketed to women. However, both men and women are decision-makers. Often, advertisers enhance stereotypes. They exclusively market or over-represent men or women in ads where the product is bought or strongly influenced by both sexes in traditional household decisions.

Further, gender-balanced brands outperform gender-skewed brands.

As more women join executive teams, brands are expected to market more gender-balanced. To support this notion, McKinsey’s 2019 analysis found that companies in the top quartile for gender diversity on executive teams were 25% more likely to have had above-average profitability than companies in the fourth quartile—up from 21% in 2017 and 15% in 2014.

African-Americans

While marketing to Hispanic Americans and Asian Americans is equally important, this article will only address African Americans. The history of marketing to African Americans is one that runs the gamut, from ignoring—even redlining—to exploitive-targeting, followed by awkward inclusion.

1940s: Jax Beer

In 1948, at the same time African Americans were being excluded from the G.I. Bill Modern Industry magazine estimated the spending power of the 14 million Black Americans at the time was $10 billion—an amount equal to that of the entire population of Canada.

Also, in 1948, Jax Beer was credited with the first commercial to target African Americans. The “Whistle Up a Party” ad is sweet, fresh, and enjoyable. It depicts three well-dressed African American couples at a house party singing around a piano and enjoying beer.

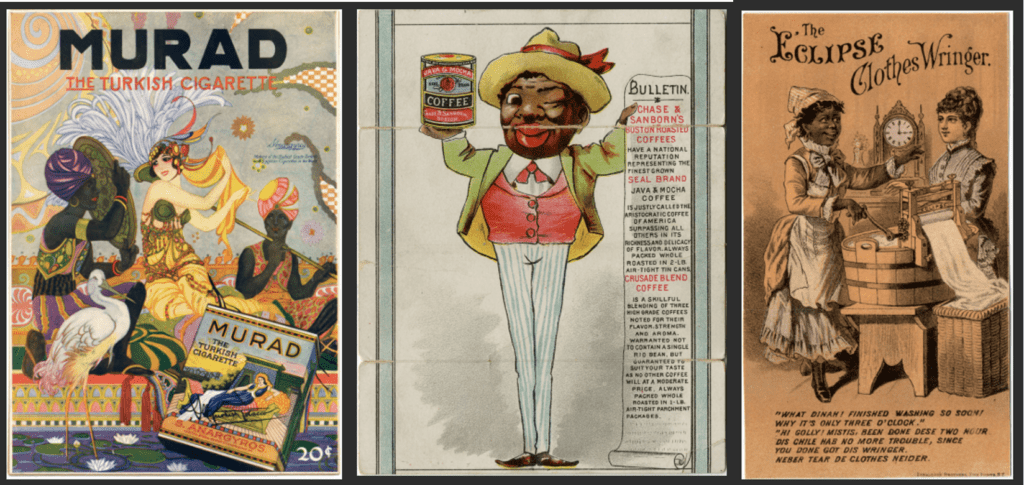

African Americans were often portrayed as subservient caricatures in ads dating back to the 1880s. They were used to represent foreign origin, authority on certain products, or expertise in household chores. However, the Jax beer ad notably marked the first instance of a mainstream brand creating an advertisement tailored specifically to the African American audience, encouraging them to spend their own money.

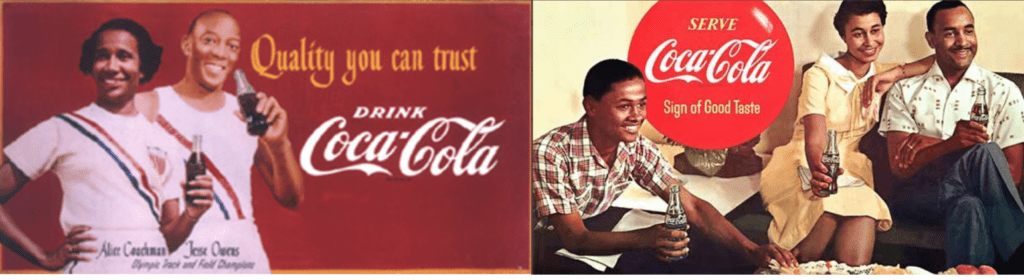

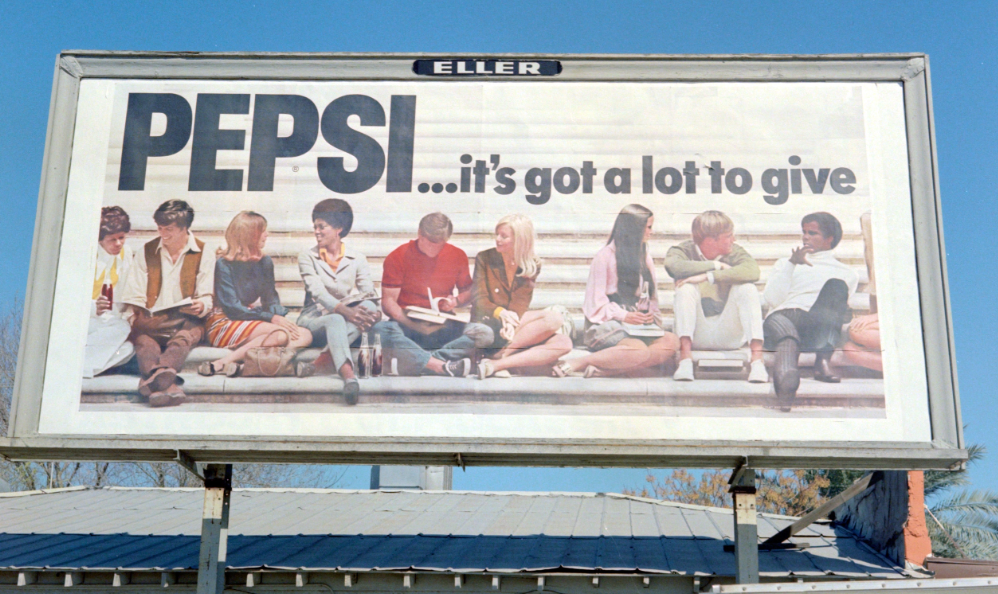

1950s: Coca-Cola and Pepsi

The Coca-Cola Company began featuring African Americans in marketing with the Harlem Globetrotters in 1951. Then, followed with Olympic Games athletes Jesse Owens and Alice Coachman in 1953. Clark University student Mary Alexander became one of the first African American women to appear in print advertising when she was featured in 1955.

Competitor Pepsi, which had hired a separate African American salesforce dating back to the early 1940s, soon followed suit. Many other mainstream marketers quickly got on board as well.

1940s–1960s: Black media and African-American models

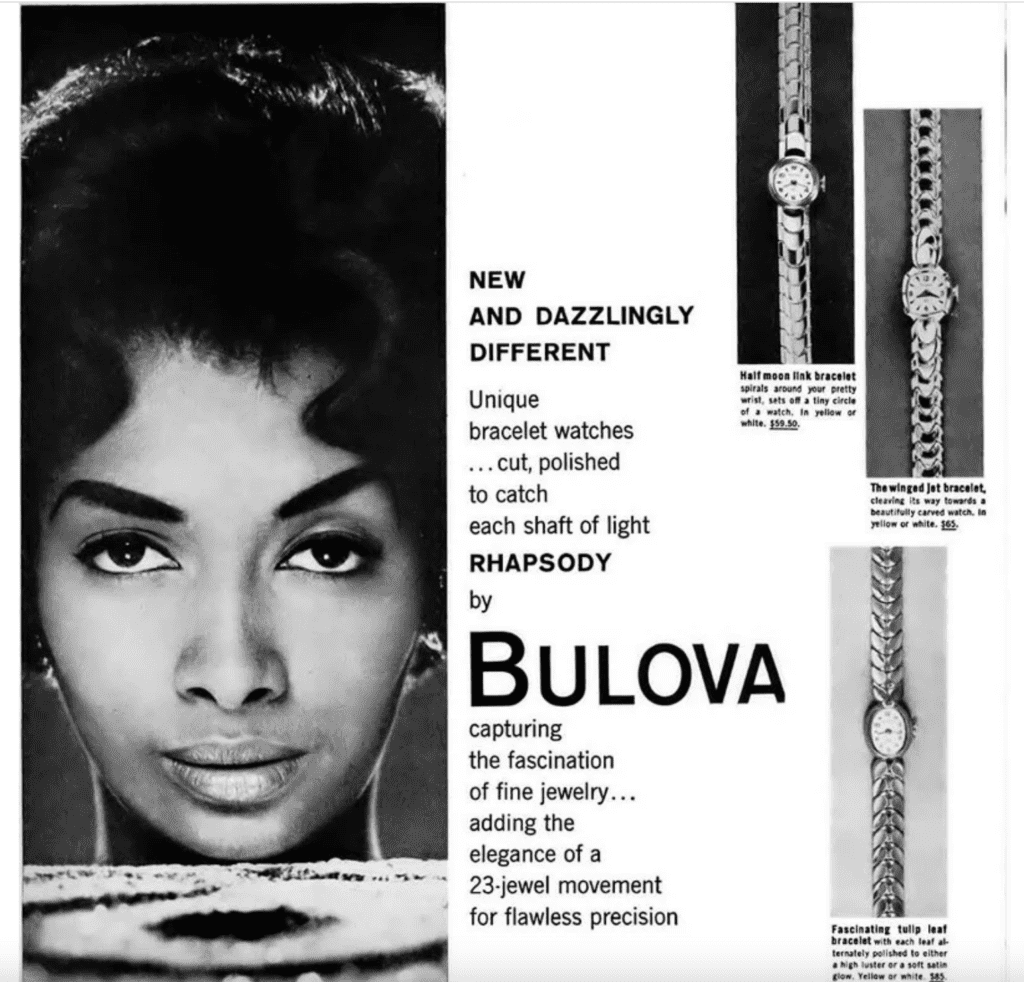

Founded in 1945 by John H. Johnson, Ebony Monthly Magazine was geared toward a middle-class African American readership. It was the first Black-oriented magazine in the United States to attain national circulation. In the 1950s, Johnson personally pitched brands to use Black models and market to his audience. By 1960, a parallel universe of mainstream and niche products targeting African Americans in ads that only ran in Black media existed. Many of these ads from the era can be seen here.

Helen Williams originally modeled for Ebony and Jet. With the desire to cross over into mainstream media, she first had to go to Paris and model for Dior and Jean Dessès before returning in 1961. With the help of journalists highlighting her challenges, she is credited as being the first African American model in the U.S. to cross over into mainstream marketing. She worked with brands such as Budweiser, Loom Togs, and Modess.

While progress was being made in advertising, the country was still under Jim Crow laws until 1965. The civil rights battle was in full swing on all fronts. People of color were having their communities targeted with interstate expansion and stadiums. So, while marketers were pursuing revenue from the burgeoning African American market, we were still mirroring and molding the society at the time. We were excluding people of color from mortgage and bank promotions, a now illegal practice called redlining.

1970s: Removing stereotypes

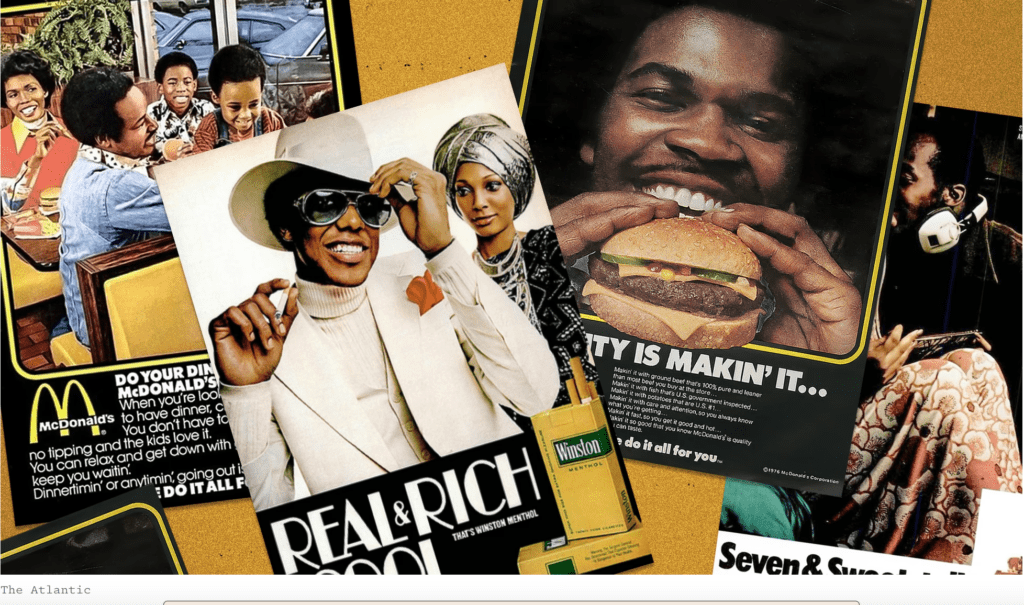

By the 1970s, ads targeting African Americans had become heavy with stereotypes, a far departure from the Jax beer ad. This Atlantic article on the topic covers it:

“Charlton McIlwain, an associate professor at New York University who specializes in race and media, said in an email that he views these tone-deaf ads as “the outcome of [advertisers] trying to do the right thing, but not necessarily knowing what that meant.” It goes on to say, “White-dominated ad agencies lacked a general familiarity with blacks and black communities, leading them” to design ads that were racially naive and necessarily relied on stereotypes for lack of any other information.”

Lenika Cruz, “‘Dinnertimin’ and ‘No Tipping’: How Advertisers Targeted Black Consumers in the 1970s,” The Atlantic

However, the 1970s also saw the beginning of inclusion ads, the most famous being “I’d like to buy the World a Coke.” This decade also saw the rise of the Black athlete/celebrity spokesman. This included Bill Cosby for Crest Toothpaste (1969), OJ Simpson for Hertz (1978), and Mean Joe Greene for Coke in 1979.

1980s–today: Tokenism

As inclusion tried to become the norm, ”Tokenism” became a problem in the late ’80s. It still carries on today as many brands inauthentically try to wedge the “Black Friend” into almost every commercial. This practice has led to disdain and backlash.

1990s–today: Interracial marriage and more

Nineteen percent of marriages in America in 2019 were interracial. Cheerios was the first national brand to cast an interracial family in a commercial in 2013. When it was originally posted on YouTube, General Mills pulled it down because the comments were so hateful.

Today, we see interracial ads every day. In a 2021 VOA article, Larry Chiagouris, a marketing professor at Pace University in New York, wrote, “It’s the brands wanting to let customers know they are listening and sensitive to their needs, many of whom are not Caucasian, and part of it is not wanting to be called out by some activists as being oblivious to people of color.”

In the same article, San Francisco State University in California Marketing Professor Subodh Bhat stated, “The public is no longer simply interested in which product might be slightly better; they also want to feel good about the company’s values.”

Whether advertising molds society or mirrors it, we can take pride in this accomplishment. What this means is that “love is overcoming hate”! It means that, as a society, the benefits of diversity and inclusion now outweigh the backlash. It may even mean that the race of an actor can be secondary to other casting factors.

LGBTQIA+

Until very recently, targeting the LGBTQIA+ community has been like the third rail of marketing. Most mainstream brands have chosen to purposely avoid it.

1910s–1970s: “Gay-coding”

While those in the LGBTQIA+ community have always over-indexed in the advertising and arts community, marketing efforts toward this community have been significantly behind. Even so, homoerotic imagery was commonplace in many mainstream ads dating back to World War I.

Pioneers like J. C. Leyendecker, who is credited with “virtually inventing the whole idea of modern magazine design,” routinely included homoerotic imagery in his ads and magazine covers. With the onset of the AIDS epidemic and the public’s anti-gay reaction, as well as the establishment of gay-centric publications, “gay-coded” ads all but disappeared by the early 1980s.

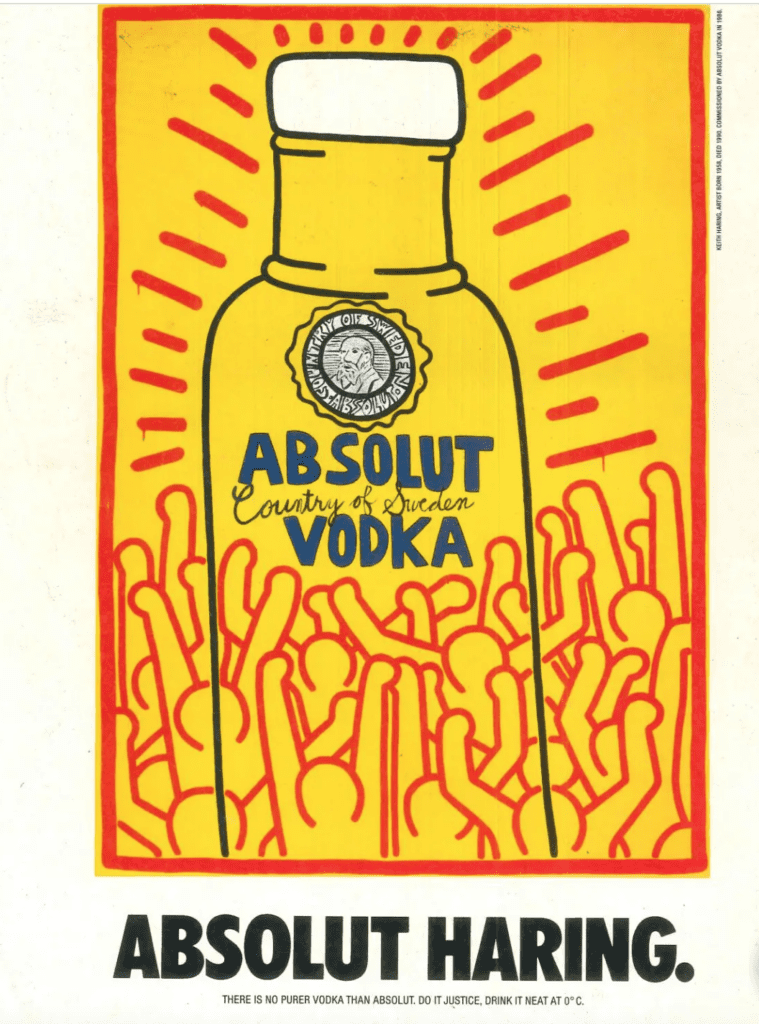

1980s: Absolut Vodka

In 1981, Absolut Vodka became the first mainstream brand to commit to full-page ads in media outlets like The Advocate and After Dark, which targeted the gay community. The ads were the same ads they were running in traditional media. However, they were just recognizing this particular audience in their own preferred media publications and supporting them with advertising dollars. In 1986, Absolut went one step further. It ran an ad created by openly gay artist and AIDS activist Keith Haring in all of its media. Most of the audience who identified as being straight had no idea. But to the gay community, it was a strong sign of support.

1990s: Subaru

In the 1990s, “gay coding” was back. Not in the form of blatant homoerotic imagery but in subtle cues obvious to this specific audience. Subaru gave a subtle shoutout to its gay and lesbian customers at the time. It featured “XENA LVR” and “CAMPOUT” and the not-well-known rainbow sticker on its cars in mainstream ads in the early 1990s.

1990s: IKEA

Many national brands saw Subaru’s success and started to include their own subtleties in pursuit of this large and growing market (Example in 2023: US LGBTQ Spending Surpasses 1.4 Trillion Dollars in 2021 – According to the Pride Co-op). But in 1994, IKEA grabbed the bull by the horns. It produced a mainstream ad about a male couple buying a dining room table.

It’s amazing this ad ran almost 30 years ago. I had the same barn jacket and everything in the ad looks time-era-appropriate. Yet I’m still amazed it ran in 1994!

Not surprisingly, the backlash was immediate and severe. Bomb threats were called into stores. IKEA calmly replied, “This is just part of our overall strategy to try to speak directly to all kinds of customers.”

2000s–today: More room to grow

While lovable gay couples in TV shows like “Modern Family” were pretty mainstream in the 2010s, laying the groundwork for the couples and families we all see in ads today, there was no such foundation in 1994. Although most companies make their logos rainbow every June for LGBT Pride Month, you mostly see just LGBTQIA+ couples woven into a montage of diverse couples and families in ads. Seldom do you see an entire mainstream ad where the main characters identify as LGBTQIA+.

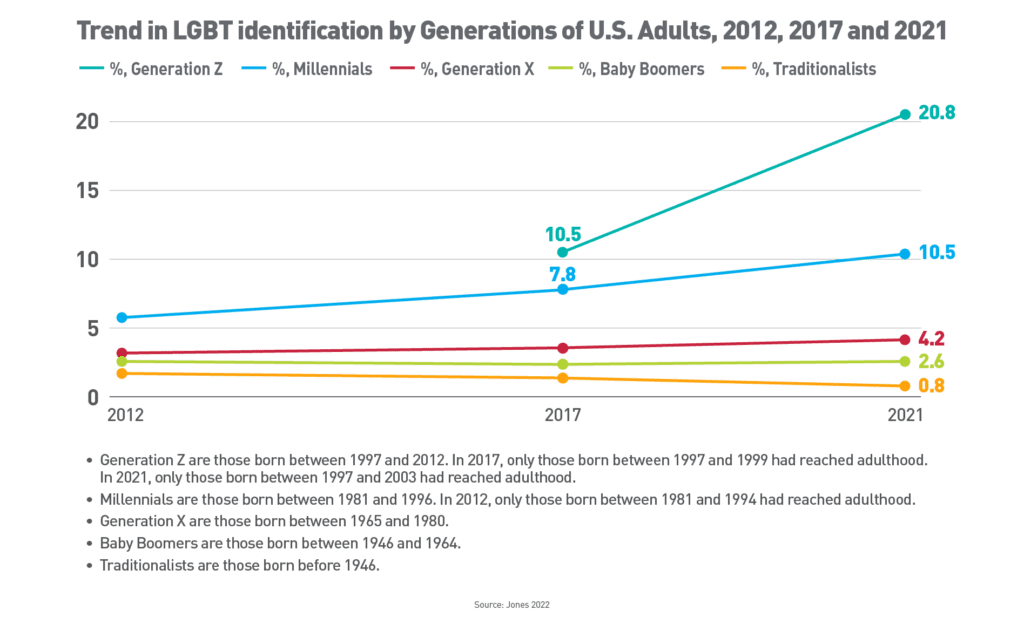

Each generation has approximately doubled its non-cisgender representation over the generation before it, with 20.8 % of GenZ now identifying as LGBTQIA+ and 71% of the public supporting same-sex marriage. Therefore, it’s safe to assume we’ll see a lot more LGBTQIA+ couples as the stars in ads.

Addressing Diversity in Marketing: 3 Questions to Ask

As we better address diversity and marketing head-on, we need to ask ourselves three questions.

- Are we acting from a place of love and acceptance?

- Are we being authentic to our brand and in our approach to customers, or are we chasing popularity?

- If culture were a wave and our brand was a surfer, would we put the brand just in front of the wave where it would crest and be ridden? Or are we putting our brand too far in front of the wave so that it’s just baking in the sun? Or are we placing the brand behind the wave and watching it go by, only to be caught and ridden by the bolder brands in front of us?

Get Expert Help With Diversity and Marketing

As advertisers, we should feel like any other group of people looking back at their past. There are things for which we should be proud and things for which we should be ashamed. Times we were strong as an industry in the face of adversity and times we were weak. And there were times we did the right thing and times we did not. Looking back helps provide us with a stronger understanding and foundation to move forward. Knowing that 10, 20, or even 70 years from now, people will be scrutinizing our actions. Will we be bold like Jax Beer or IKEA? Or will we be weak?

As with all of our articles, this one ends with an open line. Feel free to give us a call at 502-499-4209 or drop us a note here. We’re always free to chat!

Our Articles Delivered

Signup to receive our latest articles right in your inbox.